What are the âporkâ handouts at the center of a Birmingham corruption case?

Elected officials pose with giant checks, shaking hands with constituents and smiling for the cameras as they hand out public money to schools, police departments and nonprofits in Birmingham and Jefferson County.

Now the source of those grants has come under scrutiny after a federal court case revealed a kickback scheme involving two state lawmakers, a legislative aide and a youth baseball league, which prosecutors say resulted in the misuse of thousands of public dollars spent on personal credit card bills and a mortgage instead of its intended community service.

For every dollar that local residents and visitors spend in Jefferson County, one penny flows into the Jefferson County Community Service Fund, a pool of money for lawmakers to be able to dole out such grants. And while a penny might not sound like much, it adds up quickly, accounting for up to $3.6 million each year.

“It’s the old game of pork, and you give these elected officials a chance to say they did something for their constituents,” said Natalie Davis, professor emerita of political science at Birmingham-Southern College. “That’s universal.”

Since it began handing out grants five years ago, the community service fund, acting on the direction of local lawmakers, has handed out more than $16 million to organizations and cities and nonprofits across Jefferson County. Millions of dollars went to local schools, while hundreds of thousands more went to police departments, performing arts and public parks.

[Click here to see a list of every grant the fund paid out since it started five years ago]

But according to federal prosecutors, at least $197,150 of that public money wasn’t used for community service. Fred Plump, the executive director of Piper Davis Youth Baseball League, pleaded guilty in May to federal charges and resigned his seat in the Alabama House of Representatives. In his federal plea agreement, Plump implicated another legislator as part of a conspiracy to funnel public money from the community service fund through his baseball league and into personal accounts. He will be sentenced in federal court in Birmingham on Oct. 23.

Plump’s baseball league is among the fund’s top recipients, according to an analysis of the community service records by AL.com.

The committee that oversees the fund and approves funding requests said in an emailed statement to AL.com that its role is to provide accountability and transparency around how legislators issue community service grants. Donna Briggins manages the fund on behalf of the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham.

“The committee and the administrators are disheartened by even an isolated instance where the funds may have been used for anything other than their stated purpose,” the committee members said in a statement. “They have been cooperating with authorities, and they will continue to do their part to promote transparency and accountability with regard to the distribution and use of the Jefferson County Community Service Fund.”

“There has been no indication of any wrongdoing on the part of committee members or administrators,” the statement added.

Experts and longtime observers of Alabama politics say discretionary funds like this one are common and exist at every level of government — from local neighborhood associations and city councils to the U.S. Congress. In Alabama, state lawmakers from Huntsville to Mobile, Tuscaloosa to Birmingham, have access to discretionary money they can dole out to constituents.

Lawmakers commonly argue that they know more about the needs of their individual districts than the full legislature, resulting in the creation of discretionary funds such as the community service fund in Jefferson County, said Jess Brown, a retired political science professor at Athens State University.

“There’s a degree of truth in some of that. But there’s a huge political benefit,” Brown told AL.com. “They in effect get appropriated a chunk of money that they can hand out with substantial discretion. They make the timing of the handout, the venue, and place of the handout typically ripe so they can generate free publicity.”

Brown also noted that the amount of discretionary spending overall is “really a drop in the bucket” when it comes to government spending.

“There’s a public good,” Brown said. “At the same time there’s a political benefit for the individual legislator. At times they’ve done worthwhile things but the way the money flows, they also acquire a political benefit from it.”

Back in 2015, legislators from Jefferson County put together a bill to create the Jefferson County Community Service Fund. The law they passed required the Jefferson County Commission to collect the taxes that supply the fund.

Each member of the state House of Representatives from Jefferson County gets to allocate roughly $100,000 in grants each year, while each state senator gets roughly $243,000 to allocate. A committee and its external fund administrator then approve recommendations from the legislators.

For example, Rep. John Rogers, D-Birmingham, sent nearly $400,000 of his allocation to Piper Davis Youth Baseball League, according to the fund’s allocations listed publicly on its website. And, according to federal court records and AL.com interviews with some of the people connected to the kickback scheme, Plump, the founder of that nonprofit, funneled public money through the league and kicked back about half of the money to Rogers’ assistant. Plump’s federal plea agreement says the legislator, identified as Rogers, was “part of the conspiracy.”

Rogers, who said he is the second legislator in the court records, denies that he misused any public funds. Neither Rogers nor his assistant, Varrie Johnson, have been charged with any crimes related to the kickback scheme.

The federal court case reveals that the kickback scheme continued for nearly four years and involved $196,150 that Plump received for his baseball league but instead gave to the assistant.

A review of the fund’s records shows that Piper Davis is the second-highest recipient in the fund’s five-year history. Only the city of Hoover received more money than the small youth baseball league.

State Rep. Mary Moore, D-Birmingham, one of the legislators who gets to allocate funding, said the federal charges brought against Plump are evidence that the safeguards work.

“You see he got caught didn’t you? People get caught,” she told AL.com. “A crook is a crook is a crook is a crook. You have to deal with honest people.”

As part of its review and approval process, the committee checks to make sure a recipient agency has filed a 990 tax form with the IRS, a requirement for all nonprofits in the U.S. to disclose their activities, leadership and finances.

But, in the case of Piper Davis, the committee declined to say if it read the contents of the baseball league’s tax forms. AL.com found that for the past five years, the nonprofit publicly reported less than $50,000 in income annually. Yet, Piper Davis received far more than that from the community service fund alone in 2019-20, 2020-21, 2021-22, and 2022-23, according to the fund’s records and the federal court case file.

“Moving forward, the committee is likely to review its procedures to see whether additional safeguards, if any, can be implemented,” the committee said in a statement.

Accounting firm Warren Averett has prepared and published yearly reports of the fund as an external auditor since 2018. It tracks that grant funds go to designated recipients and fit within accounting principles. But it doesn’t track how the funds are used or audit the tax returns of the recipients of the funds, according to the committee. The firm’s general counsel declined to comment, citing client confidentiality.

When creating the fund, lawmakers said they were doing so to bridge funding gaps across Jefferson County.

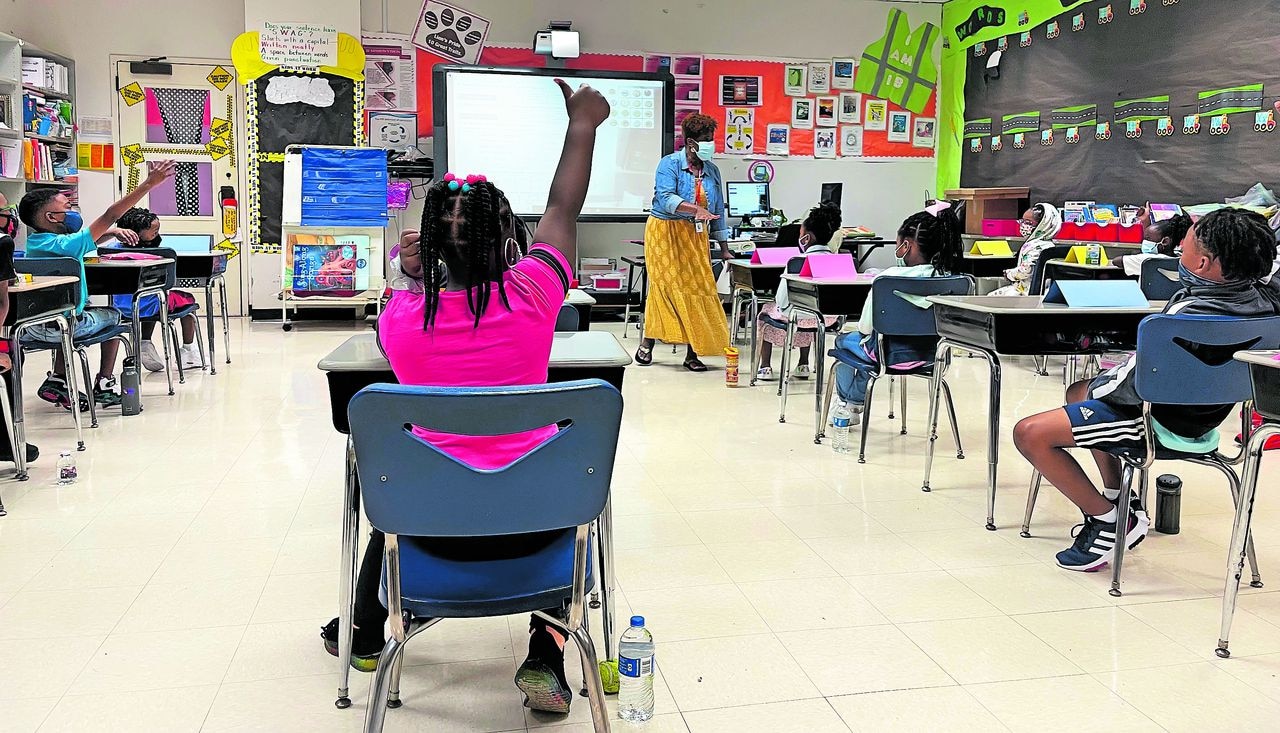

Moore originally opposed a bill in the legislature to create the fund, only relenting after legislators added an amendment to give themselves the ability to fund community needs. Most of her allocation goes to schools within her district.

“That’s when I came and supported the bill — after we came in and made sure we had something to support our schools,” Moore said. “I wanted money to go back to where they didn’t have to fundraise 24/7. I advocated for whatever we could do to get more money in our schools and into our community so we could see some results.”

The criteria for the fund requires spending on projects that “serve a public purpose,” “support that purpose, financially or otherwise,” and “benefit the citizens of Jefferson County.”

Per the legislation, funds can go to the following recipients:

- public schools, roads, museums, libraries, zoos, parks, neighborhood associations, athletic facilities, youth sports associations, sidewalks, trails, or greenways;

- performing arts;

- nonprofit entities that have received funding from the United Way of Central Alabama within the last 12 months;

- police and fire departments and the sheriff’s office; and

- assistance programs for low-income residents that use the county’s public sanitary sewer system.

This year, former State Rep. Dickie Drake, R-Leeds, set aside all of his allocation, more than $100,000, for Leeds City Schools. His reasoning was simple: his largest constituency in the county, one that he says is often overlooked, had multiple unmet needs.

“I’ve always given to every school in my district,” he said. “It is basically going toward sports programs.”

Drake said the controls and rules regarding the fund were clear.

“As far as I’m concerned, the controls work,” he said. “It was very carefully laid out as to how you could use it. It has to be approved, so I think it is working.”

While Briggins from the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham manages the fund, the committee that oversees it includes chair Sid McNeal, treasurer Chris Dorris, vice chair Samuetta Drew and secretary Sarah Mitchell. Committee members are volunteers, elected by legislators who allocate the money. The committee members are barred from holding other elected or public office.

When the fund first started allocating money, the United Way of Central Alabama handled administration of the funds. Last fall, the Community Foundation took over after the committee issued a request for proposals for a new fund manager. The goal all along was for the United Way to turn over the fund’s oversight to another entity once the fund was up and running, according to the committee’s statement to AL.com.

Moore said that a single group receiving large amounts of money over multiple years should raise suspicion. She noted that all the allocations are reported publicly on the fund’s website.

“That’s just crazy when the need in the community is just so great,” she said. “Why is one organization getting all the money, when my intention was making sure that we kept the needs of our schools and libraries in front of us?”